Article

Published: 31 Dec 2024

The Hybridity of Pattachitra Katha Media The Folk-pop Art Narrative Tradition of Bengal

Author:

Sreemoyee Majumder1 and Supriya Banerjee2,*

1 Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International University, Pune, India

2 Department of International Foundation Studies, Amity University, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed

Email: sbanerjee6@amity.uz

Article History:

Received: 14 October, 2024 Revised: 13 November, 2024 Accepted: 21 November,

Copyright

© 2024 The Author(s). Published by Content Majestic LLC

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

This paper evaluated Pattachitra Katha, a traditional cloth-based art narrative from Bengal, as a post-colonial hybrid media genre. It originated over 2,500 years ago combining visual storytelling with music and oral traditions, evolving through socio-cultural changes, globalization, and technological advancements. The study highlighted the hybridity within Pattachitra Katha shaped by processes of regionalization, indigenization, and ethinicification allowing marginalized patua artists to navigate and reinterpret their cultural identity. The paper has addressed the themes of colonialism and identity politics, particularly related to gender dynamics. Through contemporary adaptations, the genre has been relevant, transforming into a vehicle for cultural expression and communication. This article explains the emerging landscape of folk art and media, mainly Pattachitra Katha. It reflected a dynamic merger of traditional storytelling with contemporary artistic influences, that showcased a fluid link between the culture as well as technology. Such shift signified the transition from the oral and handmade types towards the digitally mediated, and international expressions, retentive to the cultural relevance. Moreover, the study explained that colonialism as well as identity politics affected Pattachitra Katha while reshaping the narrative content with style since the artists engaged with the socio-political authenticities of the colonial rule. They re-explained the folk art for asserting cultural autonomy. Such adaptation was a type of confrontation with the colonial cultural power, which helped preserve and redefine the local identities. In this regard, post-colonial theory can help to explore how colonial histories can shape artistic expressions considering the marginalized cultural types, such as Pattachitra Katha, and be a part of resistance as well as identity construction.

Keywords: Pattachitra Katha, folk-pop art, themes of colonialism, identity politics, cultural autonomy, identity construction.

1. Introduction

The Pattachitra Katha is the traditional cloth-based narrative art form from Bengal and Odisha which embodies a rich tapestry of the post-colonial hybridity in which marginalized voices are converging from the visual storytelling (Dey, 2020). It was rooted in a 2500-year history where this term intricately weaves together the folk narratives, paintings, and music that reflect the socio-cultural dynamics of its time (Sethi, 2023). With the imposing of the dominance of colonial power, Pattachitra evolved, adopting global impacts while retaining its indigenous essence. The transformation highlights the complexities of cultural identity since artists navigate between local traditions and global narratives. The hybridity of the Pattachitra is not merely adaptation but profound reimagining challenging the notion of fixed cultural boundaries.

According to (Basu, 2020), Pauta Chitra or Patta Chitra is a general term used for traditional, cloth-based painting and storytelling media genre practiced in the eastern Indian states of Bengal, Odisha, and parts of Bangladesh. Pattachitra katha is an art narrative or sequential folk narrative form of Bengal originally serving as a visual device displayed during the performance of a song or Pata Sangeet (Rohila, 2023). Patua artists enact the performances as they unfurl the painting scroll of Pattachitra by singing the tales that are painted. Through centuries, the Pattachitra and Patta Sangeet have been a genre together having different communication techniques. These are converted into visual messages, art performances, oral traditions, narration, music, and storytelling. These helped to combine, include, and portray nature, culture, and society co-existing from the lucid dialogue. As Pattachitra is a form of visual art, Pattachitra Katha refers to the narrative tradition which considers Pattachitra paintings to be a medium for telling stories (Deb, 2020). Moreover, Pattachitra Katha tends to bring static paintings to life through storytelling, as per which, all the painted panel over the scroll shows a part of the story. As times changed, Pattachitra Katha as a genre of mass media and cultural communication adopted global transformations with the expansion of knowledge systems, global outreach, and technical support. Automatically the transformation came into the intangible sector of its small tradition as folk media. The Pattachitra tales with the help of intertextual connections of global concepts, themes, news, and popular narratives changed their mode and grew as new media (Choudhary et al., 2024). For the last twenty years, modern transformations have come into Pattachitra Katha through a practice of thematic hybridity within its expression of the older traditions in the new modern media.

The paper explores the evolution of Pattchitra Katha, focusing on its role as a medium of cultural communication and a vehicle for social change. The research has obtained insights about how this art form continues to resonate within contemporary discourse evaluating the interplay of tradition and modernity. It highlights its significance as both a historical artifact and a living practice engaging with today’s globalized world. A considerable theoretical framework to analyze the emergence of Pattachitra Katha in colonialism and identity politics case can be Postcolonial Theory which is combined with the Cultural Studies (Mongia, 2021). The framework explains how the colonial histories form the artistic expressions where the marginalized cultural forms, such as resistance of Pattachitra Katha, and identity construction (Cooper, 2020). It can even use the concepts from Hybridity, given by Homi K. Bhabha that pay heed to the merger of traditional and modern influences, with Cultural Hybridization in the media (Kuortti, 2020). Overall, the article has contributed to discovering Pattachitrakatha hybridization while blending traditional folk art with modern media. It has also examined the role of the cultural resistance with the identity politics. However, a gap exists in terms of analyzing the detailed effects of digital platforms on emergence and how international trends even shape such folk-pop narrative tradition.

2. Methods

This paper uses qualitative content analysis that focuses on the use of secondary sources to evaluate Pattachitra Katha’s cultural significance and hybridity (Chatterji, 2020). The analysis of the range of literature including academic articles, art critiques, and historical documents helps research in identifying recurring themes, narratives, and transformations within the Pattachitra tradition. The approach helps in a comprehensive understanding of how the genre has adapted over time responding to colonial influences and globalization. The content analysis helps in evaluating the visual texts and their socio-political contexts, indicating how marginalized voices are articulated in this art form (Spencer, 2022). Furthermore, it provides insights into the interplay between traditional practices and modern interpretation elaborating the dynamic nature of Pattachitra Katha as the medium of cultural expression.

3. Analysis

3.1. Post-colonial Ethnic Folk-Pop of Marginalized Artists

In post-colonial cultures, instances of deliberate cultural repression give rise to hybridity (Tetik, 2020). Naturalized mythologies of racial or cultural origin frequently serve as the foundation for the concept of nation. The nature of post-colonial culture has hybridized the media production of post-colonial art (Gruber, 2024). When a colonial power invades another country in an attempt to establish its dominance over the economy and politics, it destroys the culture of the colonized people and forces them to adapt to new social norms. Pattachitra which as a media genre has always been a cultural hybrid, with the emergence of global reality through the stage of social evolution, from national to global level, has been influenced by migration, religious and political invasion, adaptation, and of course hybridization (Majumder, 2020). The hybridization of folk media is a complex process of unitary fragmentation. The fragmentation of the public sphere of knowledge production and ethnification of regional cultures. The hybridization of Pattachitra Katha includes three different processes of fragmentation- indigenization of global concepts, regionalization of national narratives, and ethnification of folk or popular culture. Pattachitra ‘s artistic practices emerged considering the colonial histories with the adaption of traditional folk stories for asserting the cultural identity while resisting colonial dominance (Ceciu, 2021). At the time of British rule, Pattachitra artists had added themes of the local resistance, which reinterpreted the religious along with the mythological stories to emphasize the indigenous autonomy. Such adaptations showed an amalgamation of the colonial as well as Indigenous influences and marked Pattachitra hybridization in the form of cultural resilience with a tool to maintain the identity considering the external pressures.

Fig. (1). Painting Influenced by Kalighat Patachitra, Artwork: Saptarshi Dey, Source: Karmakar et al. (2020).

As shown in Fig. (1), the media genre originated from rural Bengal and came to the Kalighat area with the migrated Patua artist community of the marginalized caste groups and stemmed from the changing world of 19th century Kolkata. Over there, the traditional techniques of painting, iconographies, and art practices were connected with Mughal court culture, Bengalee Babu culture, British public lives, the Swadeshi movement, theatre of proscenium stage and lithographic presses subsequently (Karmakar, 2020). The folk media transformed into popular urban media. The birth of Kalighat Pattachitra happened leaving a cultural hybridity practice forever alive. The advancement of mass lithographic painting in Kolkata suddenly increased the demand for cheap commercially produced visual art. The culture industry of new age Indian image soon signaled the sudden end of Pauta’s trade of hand-printed art. Here comes the third category of Pattachitra production. The testimonial Pattachitra production was the new practice of Patua hybridity (Rajadurai, Krishnamoorthy & Saravanakumar, 2020). It carried the journalistic essence inside. The news of the city of Calcutta used to be served to the villages. The woodcut paintings were also in the market which were greatly influenced by the Kalighat Pattachitra. Kalighat Pattachitra turned into a memento of the temple visit of the upper-class Bengalees. A residential locality was created by the Patua artist community who moved from rural Bengal to the temple around area. An art market was created along with the industry and the necessity. This can be well understood through an example of the testimonial Pattachitra production which is a series made by the artists in the 19th century for documenting the effects of British colonial rule over Bengal. Such scrolls showed a glimpse from the News of the City of Calcutta, that illustrated the urban transformations, colonial structures, and the emerging socio-political landscape under British influence (Skains, 2022).

After Pattachitra Katha’s folk production, industrial production emerged and the marginalized population participated in the contemporary urban art practices. The struggle that started between cosmopolitan versus locals or ethnic versus nationals turned into the cultural identity of a larger landscape called ‘Bengal’ or ‘India’ from the locals (Sugathan, 2024). This way the popular folk hybrid Pattachitra was the need of art hunger and cultural psyche. The classical concept of folk is all about a small society with relatively well-defined cultural borders with internal cultural homogeneity, coherence, and continuity. But the folk media of Pattachitra Katha tradition deconstructs such validation or notion of culture concept. The identity space of Pattachitra folk art media through its process of multicultural adaptation and hybrid storytelling established itself as a global ethnic. Multi-culturalism of Pattachitra communication diminishes the classical concept of culture is the breaking up of the territorial cultural borders and ethnic groups from different varieties. The theorization of the hybridity of Pattachitra Katha is another need to critically understand the Indian folk media in a better way.

3.2. Understanding of Pattachitra Katha’s Hybridity and Identity

The question of hybridity significantly involves the question of identity politics and gender of the Patua artist as well. Because the gender of the Patua artist has its influence on the media politics of the Pattachitra market and testimonial form of the genre, “the great creative eras are those in which the communication had become adequate for mutual stimulation by remote partners, yet was no frequent or so rapid as to endanger the indispensable obstacles between individuals and groups or to reduce them to the point where overly facile exchanges might equalize and nullify their diversity” (Levi-Strauss, 1985).

For various reasons, including their longing for a lost racial identity, anthropologists have always been deeply committed to preserving the integrity of civilizations. Franz Boas’s emphasis on the ethnographic urgency also highlights the hybridity practice, which Levi-Strauss described in 1973 as “our filth, thrown into the face of mankind” (Levi-Strauss, 1973). Geertz (2012) contends that Levi-Strauss’s perspective reveals a common method of viewing cultural diversity as an alternative to ourselves, appropriate for a world in which a great number of distinct and unique cultures were only tangentially connected, maintaining a respectful distance and occasionally exchanging mildly reciprocal messages. Levi-Strauss (1985) explained the concept of the differential gap between two cultures as a creative encounter.

Fig. (2). Spiderman in Pattachitra, Courtesy: Yantrapurush, Source: Sanyal (2022).

Any art media production of any colonized community or society is a cultural production by a colonized mind. Patua artist’s mind is colonized multiple times by multiple influences of time, age, culture, and place for two thousand years. The process of decolonizing is a re-creative experimentation (Levi-Strauss, 1985). A Patua artist can cross the barrier when he or she refuses to be ghettoized and through the complex and combined essentialisms of gender, race, or ethnicity. Fig. (2) shows a picture of Spider-Man in Pattachitra, giving an example of cultural hybridity, mixed with traditional Indian folk art along with international pop culture. The picture connects him to the overall cultural as well as spiritual themes based on heroism in Bengali or even Indian folklore, which creates a fascinating dialogue between the old and new (Sanyal, 2022).

There is an endless discussion of the concepts of ‘other’ and the ‘difference’ that can establish an integral relationship between creative productions and the theories that validate the challenging deconstruction of power politics. Fanon’s concept that ‘decolonizing is always a violent phenomenon’ is useful for building up any cultural community’s identity (Levi-Strauss, 1985). The cultural and psychological violence perpetrated by the colonizers is appropriated by the Post-colonial Patua artist women’s discourse. The violence involves the colonization of minds, myths, aesthetics, and popular practices. Pattachitra Katha art media has gone through innumerable colonizations and resulted in multidimensional hybridity.

The hybridity of a Pattachitra text creates a cultural landscape which is the creative field of encounter between two cultures ensuring the birth of ‘glocal’ (Geertz, 2012). Hybrid Pattachitras either overtly or implicitly represent a perception of the world outside and inside the geographical and cultural landscape of India and also re-create characters within that world. Often the Patta Katha revolves around the narrative which is always a new narrative or may be a thematic hybrid. Three ancient media genres visual narrative, oral narrative, and musical narrative, reframing and colonizing each other together. The activation of a media space and virtual installation of an environment among both the performers and audience immediately happens in a performative way that is theatrical. The significantly complex and essentially problematic interaction of Pattachitra Katha’s performance also tries to explore the aesthetic potential of the ‘new present tense’ of the narrative (Geertz, 2012).

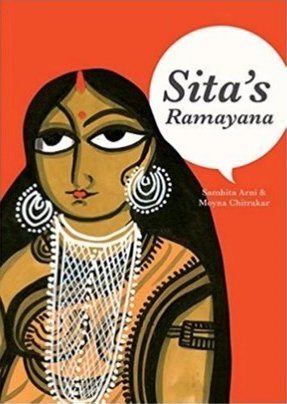

The audience encounters either immediate or virtual reality for an altered reality. They watch Pattachitra texts and immediately get into the mise-en-scène (theatrical production arrangement) of the visual image which may not have any historical reality-based or mythical connection with the culture. The ‘here and now’ folk aesthetic dimension of the performative art of Pattachitra katha frames a visual interaction with the audience claiming a slow move towards the aesthetics of virtual reality or dramaturgy. How can Pattachitra katha be claimed as multi-medial? The five characteristics of virtual reality – integration, interactivity, hypermedia, immersion, and narrativity altogether form a discourse that is interdisciplinary and inter-medial (Falah et al., 2021). The generic revolution and transformation happened when Sita’s Ramayana was created as a graphic novel based on Pattachitra Katha of Maya Chitrakar. Maya Chitrakar’s Sita’s Ramayana is linked to Virtual Reality by its impressive artwork, engaging narrative, and various perspectives (Rohila, 2023). Similar to VR, it tends to collapse time, and offer a modern retelling that links with the ancient mythology considering the modern visuals. This allows the readers to be a part of the story in contrasting ways. Fig. (3) depicts the traditional art with modern storytelling.

Fig. (3). Sita Ramayana based on Pattachitra Katha of Maya Chitrakar, Source: Rohila (2023).

When modern media penetrated isolated areas of art practice, the older forms tried to maintain their validity, particularly when media tried to influence art’s attitudes, instigate art’s actions, and promote change. It happened in the case of the Pattachitra industry. When the 2500-year-old media of Pattachitra becomes digital and global, the texts could no longer remain old and marginalized. The surprising adaptation of newness created a new necessity within the form to create a new visual grammar for the sake of economic expansion as an industry (Zantta and Roy, 2021). The formation of a hybrid pattachitra discourse is also an industrial interest.

3.3. Industrial Need for Hybridity

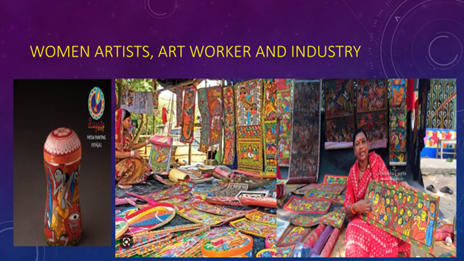

A Facebook advertisement shows a Warli folk Painter who does not have a customer and Facebook’s digital marketing asks him to change the media from wall to clothes (Khandekar, 2019). Then he becomes successful. The hegemonic influence of industrial power and market politics did not miss the fact of creating a market of digital marketing folk art media. Most interestingly, promoting the role of women artists in folk art production is another industrial marketing strategy. In a meta-critical way if we investigate this transformational forever newness of the folk media Pattachitra it questions the provocation for hybridism of an art production within its content and the genre. And the post-medium condition of art production and its discontents is also questioned as well. Pattachitra Katha both as industrial production and contemporary new old art media genre can be referred to as interdisciplinary and hybrid in terms of cultural influence and contents as G. Stocker and C. Sommerer described hybridism in art as “re-contextualization of the means, forms, and genres of artistic expression, escalating battles to prevent contamination of the self by the other”. The advantageous opportunities of this genre being alive from 2500 years ago to be in digital culture also help this form to correspond to epistemological and ontological transformation. The Pattachitra culture industry also remained the entertainment business for this long. Its control of consumers is mediated by entertainment and its hold was not broken because of the hostility inherent in the principle of entertainment. The value of the embodiment of gendered human figures always added some more to this entertainment industry. There is always the absence of the original in this Pattachitra industry like in any other folk art industry. The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity. Now, the question is, an industry that is based on easily imitable art how can be interesting even in the digital age? Or the digital time again creating a new market for the handicraft industry? The Pattachitra industry is an emancipation of various art practices from ritual to go increasing opportunities for ages. Even in the digital market, it created its significance within mechanical reproduction. From the quantitative shift, the genre went to the qualitative transformation. The greater the decrease in the social signification of an art form, the sharper its distinction between criticism and enjoyment by the public. For so long the genre, even as a media form or art product did not ask for critical insight.

Pattachitra industry while going through transformations also creates new age artist labourers as other folk medium in the global market. In Banglar Pot O Potua, Dr. Aditya Mukhopadhya (2017) stated that Patuas could not develop as artists, they developed as painters and laborers. In The Author as Producer Walter Benjamin (1969) denotes that the author as producer can fight with the proletariat by betraying his class origins and the mode of production whence his work arises by changing technique and apparatus (Adams, 1969). A Patua artist as a member of a society inexorably should address class struggle but he is also a part of an industry whose framework is defined by the mode of production and capitalism (Kar, 2024). The proletariate Patua Chitrakar who stands as an author of Pattachitra texts also delineates himself as an agent of local industry and class representative as in Folk Media and Rural Development Dr. Harish Kumar (2006) clarifies. The increasing number of women Patua artists and their global view and connections with the internet also gave hybridized expansion to the Pattachitra texts as shown in Fig. (4).

Fig. (4). Folks and Rural Development, Source: Edward A. Shanken (2010).

In Contemporary Art and New Media: Toward A Hybrid Discourse Edward A. Shanken (2010) clarifies that new media does not only offer expanded possibilities for art but also offers valuable insights into the aesthetic applications and social implications of technology. Dr. Mukhopadhyayin his Banglar Pot O Potua (2017) describes Pattachitra Artists as a class belonging to the marginalized Patua community of Bengal. The discourse of the visual narrative produced from the margin always has its semiotic version of everyday history. Semiotics and Art History: A Discussion of Context and Senders by Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson (1991) denotes how Art history changed the discipline history itself radically and took the linguistic turn to approach images with the context of an age. Modern art history is examined today with a semiotic perspective and status of meaning. Since semiotics is a fundamental trans-disciplinary theory, art and performance have their grammar and Pattachitra Katha is not an exception. In the dialogic communication between Pattachitra art and the audience, the author or artists stand at the sender’s end and the audience or the buyers are at the receiving end. In between there stands the industry. Here are Pattachitras narrating stories of the films Titanic, Avatar, and Harry Potter. The powerful media of cinema took over the market and the Pattachitra themes never lost their ethnicity of discourse even when it is global and modern (Harty, 2020). Fig. (5) shows the blend of traditional art with the global pop culture, that creates cultural hybridity.

Fig. (5). Pattachitra narrating stories of Titanic, Avatar and Harry Potter, Source: Harty (2020).

Along with the media tradition itself, the industry’s market went through repeated transformations ranging from the local village art production to urban entertainment school, from hand-craft to lithograph and digital printing on paper, clothes, or other objects. So, genuinely the media standard went through identity surrogacy or thematic hybridism. So, in the Pattachitra culture industry, this imitation becomes absolute. The cultural landscape of the Pattachitra media genre creates “indeterminate trajectories” within which the unrecognized producers, poets, singers, and Painters remain the invisible art laborers (John & Mathews, 2023). This media market does a secondary colonialism in the global market with its hybrid themes. The doctoral study intends to work on the grassroots renaissance (John A. Lent) based on the modern messages of Pattachitra Katha media which is rich in variety, readily available at low cost, and relished by different age and cultural groups.

3.4. A Hybridized Version of the Everyday Myth in Pattachitra

The hybrid version of Pattachitras is a reconstruction of regular myths or everyday history of the globe establishing the identity of the art and the community of Patua artists (Sanyal, 2022). In terms of creating and representing magical, mysterious realism of the collective memory and oral narratives of the cultural landscape of Bengal, Pattachitras manifest messages and meanings. Mythologizing and mystification are artistic procedures to narrate cultural beliefs and truths since myth has its stolen language and works as a mode of communication that signifies realism. In Myth Today, Barthes said that it takes a special condition that is needed by the language to become a myth (Al-Kadi & Alzoubi, 2023). “But what must be firmly established at the start is that myth is a system of communication that is a message. This allows one to perceive that myth cannot possibly be an object, a concept, or an idea; it is a mode of signification, a form.” Now, it is the testimonial power of discourse or, human history that converts reality into speech. The mythical language of Pattcahitra does not help the objects evolve from the nature of the things but gives them a form. In, this way, speech becomes a message. Myth as a semiological discourse-making or meaning-making system undoubtedly depends on the idea of signifier and signified but there Barthes finds a tri-dimentional pattern which also adds sign to the list. He denotes the semiological chain from which myth is constructed and calls myth a “second-order semiological system” (Al-Kadi & Alzoubi, 2023). The mythical speech of Pattachitra discourse always ends up with the status of mere language and is reduced to a pure signifying function.

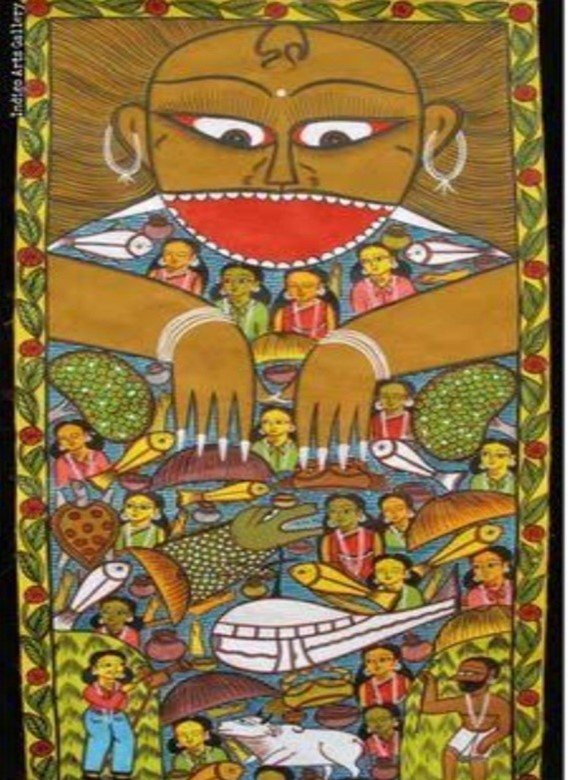

Here it is Pattachitra signifying Tsunami, 2004 as a demon of water grasping everything and everyone (Orenstein, 2023). To the village artists who never had any idea or knowledge of high floods because of earthquakes, it was fascinating and difficult to create a sign system or signifier or signified for them. They created a water demon who came to gobble up everything. The frame with natural flora and fauna represents nature. The women, the fishes, crocodiles, animals, houses every single existence is under the demonic grasp of water. A helicopter comes to rescue and a journalist comes to take photographs. Fig. (6) shows the damaging power of nature, which blends with traditional art and modern ecological themes and symbolizes loss with resilience.

Fig. (6). Pattachitra signifying Tsunami, Source: Orenstein (2023).

Conclusion

Claiming the need for a detailed theoretical study of the hybridity of Pattachitra discourse is the best way to conclude it. This article has explained the nature and expansion of the hybridity of Pattachittrakatha art media and its everyday intention to be the complex critical art discourse claiming theoretical research in this area. The history of repetitive political and cultural colonization of the art practice and the cultural identities precludes the fact of the genre’s hybridity ensuring the conclusion of its profound way of hybrid myth-making keeping the process of ethnic semiotic discourse building intact.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Declared none.

References

Adams, R. M. (1969). Weimar Elegies. https://doi.org/10.2307/3849237

Al-Kadi, T. T., & Alzoubi, A. A. (2023). The Mythologist as a Virologist: Barthes’ Myths as Viruses. Philosophies, 8(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies8010005

Bal, M., & Bryson, N. (1991). Semiotics and art history. The art bulletin, 73(2), 174-208. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045790

Basu, J. K. Reviving Tradition in Contemporary Storytelling: Visual and Oral Techniques in Sita’s Ramayana and Adi Parva: Churning of the Ocean. Managing Editor, 71.

Ceciu, R. L. (2021). Language and Intermedial Metamorphoses in Indian Literature and Arts. In Collected Papers of the 21st Congress of the ICLA (p. 551). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110642056

Chatterji, R. (2020). Speaking with pictures: Folk art and the narrative tradition in India. Routledge India. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367818340

Choudhary, S., Kumar, S., Bhagchandani, P., Banker, A., Gaur, S., & Chandra, S. (2024). Crafting Heritage: A Journey through India’s Artistic Traditions. LWRN Studio.

Cooper, F. (2020). Postcolonial studies and the study of history. In The new imperial histories reader (pp. 75-91). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003060871

Deb, B. (2020). The Role of Philately in Art Storytelling: The Case of Ramayana.

Dey, A. (2020). HISTORICIZING MARGINALITY IN GRAPHIC NARRATIVES: INDIA AND BEYOND.

Falah, J., Wedyan, M., Alfalah, S. F., Abu-Tarboush, M., Al-Jakheem, A., Al-Faraneh, M., … & Charissis, V. (2021). Identifying the characteristics of virtual reality gamification for complex educational topics. Multimodal technologies and interaction, 5(9), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/mti5090053

Geertz, C. (2012). Available light: Anthropological reflections on philosophical topics. In Available Light. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400823406

Gruber, A. (2024). Time and the (Post) colonial Self: Oppressive Uses of Time and the Construction of Postcolonial Identities (Doctoral dissertation, Friedrich-Alexander-Universitaet Erlangen-Nuernberg (Germany)). https://doi.org/10.25593/open-fau-913

Harty, K. J. (2020). James Bond, A Grifter, A Video Avatar, and a Shark Walk into King Arthur’s Court. Arthuriana, 30(2), 89-121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27125843

John, E. S., & Mathews, A. P. (2023). Media Technology and Cultures of Memory in India. Media Technology and Cultures of Memory: Mapping Indian Narratives. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003350330

Kar, D. (2024). Conflict Zone Literatures: A Genre in the Making. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003320098

Karmakar, A. STYLE OF STORY BOARD: AN ENCOUNTER WITH KALIGHAT SCROLL PAINTING.

Khandekar, N. (2019). Globalisation and its effects on the Warli art. Journal of Social Inclusion Studies, 5(2), 193-199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2394481119901072

Kumar, H. (2006). Folk media and rural development. Indian Media Studies Journal, 1(1), 93-98. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003269670

Kuortti, J. Hybridity in Postcolonial Literary Contexts. In Engagements with Hybridity in Literature (pp. 90-118). Routledge.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1973). Tristes Tropiques. Paris: Plon. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520352131-022

Levi-Strauss, C. (1985). The View from Afar. New York: Basic Books.

Majumder, R. (2020). Syncretic imageries in narrative patachitra of Bengal: A case study. Academic Discourse, 9(1), 115-125.

Mongia, P. (2021). Contemporary postcolonial theory: A reader. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003135593

Mukhopadhyay, A. (2017). Banglar Pot O Potua.

Orenstein, C. (2023). Reading the Puppet Stage: Reflections on the Dramaturgy of Performing Objects. Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003096627

Rajadurai, G., Krishnamoorthy, K., & Saravanakumar, A. R. A STUDY OF HISTORICAL PAINTINGS INSPIRED BY INDIAN REGIONS.

Rohila, B. (2023). Graphic Novels and Traditional Art Forms: the Indian Context. Indialogs, 10, 11-26. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/indialogs.218

Sanyal, D. (2022). Economies of Longing: The Superhero as National Leader in India (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oregon).

Sethi, B. (2023). Cultural Sustainability: Influence of Traditional craft on Contemporary craft cross-culturally.

Shanken, E. (2010, June). Contemporary Art and New Media: Toward a Hybrid Discourse?. In conference “Transforming Culture in the Digital Age,” Tartu Estonia, April (Vol. 15, p. 10).

Skains, R. L. (2022). Neverending stories: The popular emergence of digital fiction. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Spencer, S. (2022). Visual Analysis. In Visual Research Methods in the Social Sciences (pp. 194-236). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203883860

Sugathan, A. (2024, September). The Emergence of Comic Art and Graphic Narratives in India. In Comics| Histories (pp. 21-54). Rombach Wissenschaft. 10.5771/9783988580566-21

Tetik, S. (2020). Postcolonial International Relations Theory: The Concept of Hybridity.

Zanatta, M., & Roy, A. G. (2021, August). Facing the pandemic: A perspective on patachitra artists of West Bengal. In Arts (Vol. 10, No. 3, p. 61). M https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10030061